The Road from Damascus begins almost imperceptibly: with a family meal and an unexpected guest. Into the house enters a migrant, wounded and mute, who is given the name Petko. His silence, at first only a sign of weakness, soon grows into the central element of the play. As the family members try to care for him or interpret him, each of them in fact reveals their own frustrations, fears, and repressed desires. The home, at first a safe and familiar place, becomes a space where the entire spectrum of reactions to the presence of the Other is drawn out.

The play is divided into three parts — Logos, Abyssos, and Agape — which also trace a path: from language to silence, from family harmony to disintegration, from violence to the fragile possibility of love.

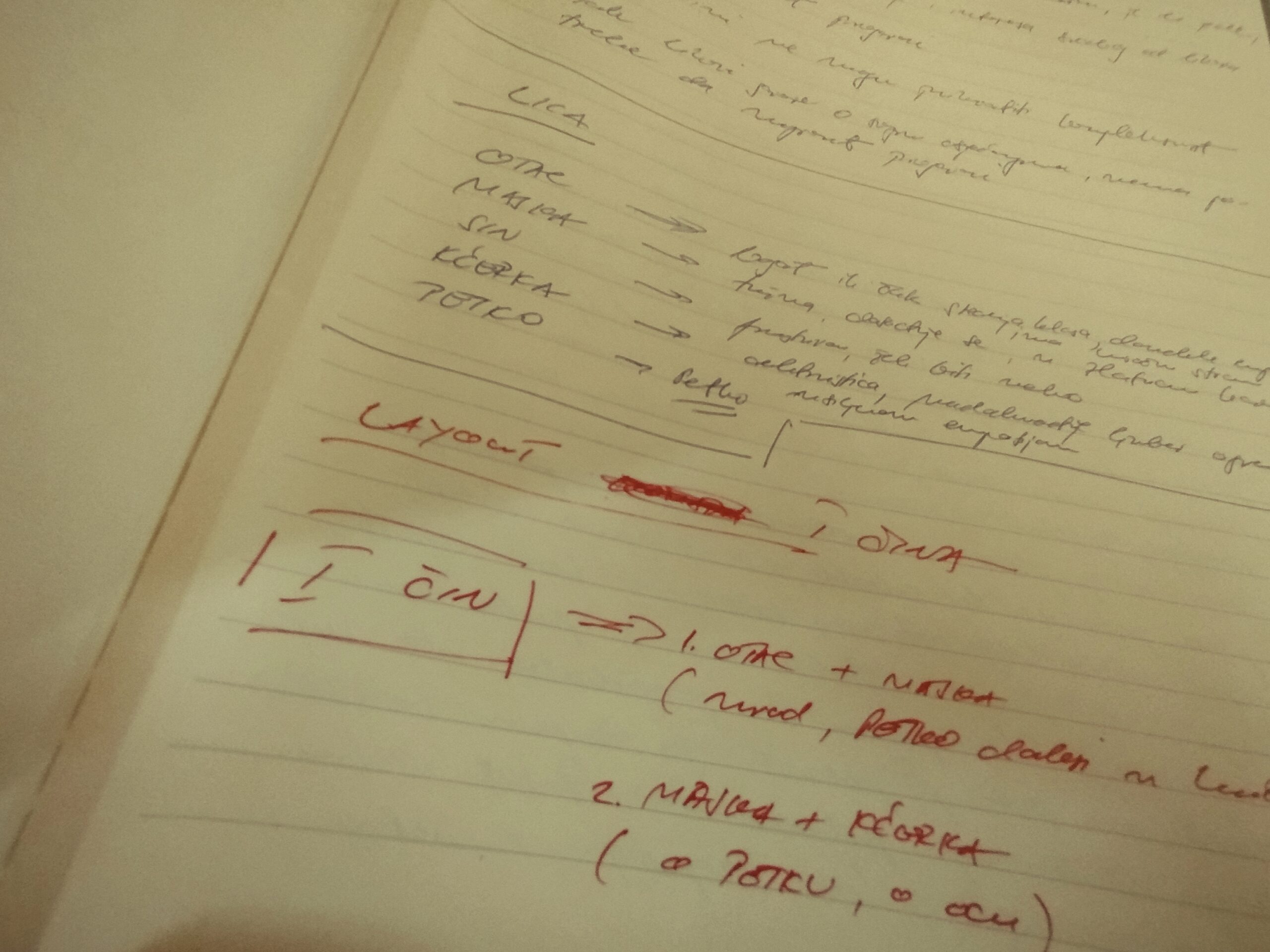

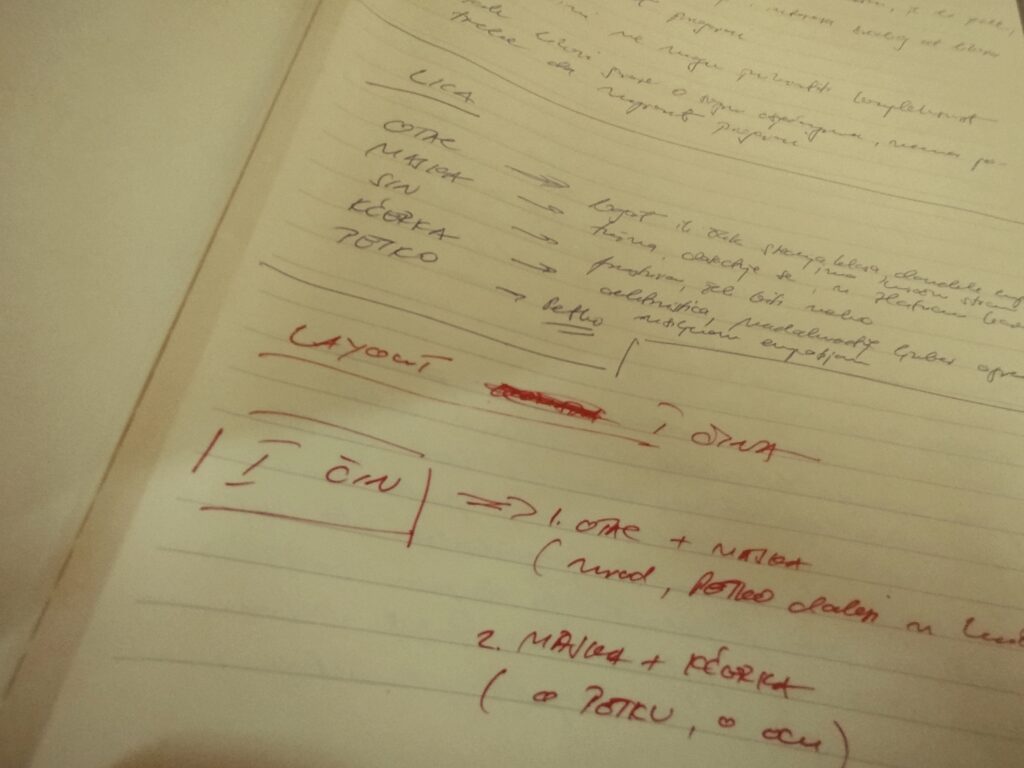

In the first part, Logos, everything is in speech. The family engages in endless conversations, often banal, about food, trifles, everyday life. But behind those words lies constant tension: the father as a figure of authority, the mother as guardian of the appearance of normality, the children balancing between rebellion and defeat. Their speech becomes increasingly aggressive, as if they want to fill the void of the migrant’s silence. He says nothing, but it is precisely this “nothing” that compels the others to speak more and more loudly, exposing what otherwise remains unspoken.

The second part, Abyssos, takes the action into the basement — both literally and metaphorically. Here what has long smoldered is revealed: violence, hatred, and the need for total domination. The everyday faces of father, mother, son, and daughter disappear; in their place emerge figures that personify the wider mechanism of repression. The migrant, once a powerless guest, becomes an object of control. Care turns into torture, hospitality into mockery, and the line between apparent kindness and open brutality collapses. The basement becomes a dark stage of human helplessness and aggression.

The third part, Agape, brings a change of tone. Petko finally speaks — but not in ordinary language; rather, through stories that invoke the mythical and the parabolic. He becomes a storyteller of fables and parables, bringing into the house tales of Majnun and Khidr. His words open a space in which violence is not erased but complemented by the possibility of love. Agape is not sentimental reconciliation, but a vision of love as the last line of defense against disintegration, as the only path toward something that transcends hatred and fear.

The Road from Damascus is a play in which a small family scene expands to universal proportions. The migrant, mute and wounded, stands at the center as a figure who draws from others what they themselves do not wish to see. His silence produces speech, his presence produces violence, and his later storytelling opens the possibility of transformation. The play thus becomes a parable of society: of how fear of the Other turns into hatred, how violence is often justified as care, and how love remains the last, fragile, but irreplaceable alternative.

Ultimately, The Road from Damascus offers no solutions or moral lessons. Its strength lies in the way it draws an entire cosmos of tension out of everyday scenes: between language and silence, family intimacy and political violence, the banal and the mythical. It is a play that does not ask the audience or reader to find a way out, but to remain within that fissure, confronted with the question: what remains when all the masks of language and power are exhausted, and is love truly possible as the last refuge?