Calderón’s hero Sigismundo, imprisoned all his life, is granted a single day of freedom. His jailers drug him and transfer him to the royal palace, where Sigismundo awakens dressed in splendid garments. The courtly entourage informs him that he is a prince and heir to the throne. Deprived for years of life’s pleasures, Sigismundo becomes violent, demanding his right. Terrified courtiers drug him again and return him to his dungeon. Sigismundo awakes, believing that the day in the palace was nothing but a dream.

A Transcendent Mission

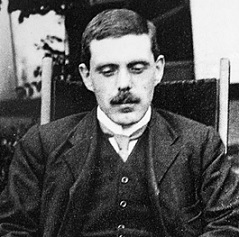

David Lindsay had, metaphorically, slept for twenty years. Two decades he spent climbing from office clerk to financial specialist at Lloyd’s. In his fortieth year, as if called by some otherworldly mission, he abandoned London and his petty bourgeois life to become a professional writer — without connections, without experience, armed only with erudition, imagination, and a dream that had burned within him for two decades.

Perhaps such a radical decision was shadowed by death: mobilized during the First World War, Lindsay never saw a battlefield, but he smelled the stench of military squalor. Shortly after the war, his elder brother died prematurely; though they had not always been on good terms, Lindsay sat at his deathbed. He broke off a fourteen-year engagement and married a woman he had met only months earlier. The couple moved to mystical Cornwall, and Lindsay set to work, convinced that he had donned the perfect garb of a writer: desolate moors, cloudy skies, and the myths of the provinces.

The Perfect Garb of a Writer

Undoubtedly he dreamed of glory. More than that, he dreamed of great, genius books. He saw himself standing alongside Hardy and Shaw. With that fervor, deep in the Cornish mists and northern myths, he began his first novel. He wrote feverishly, certain he was crafting a great book, one he had been rewriting in his head for ten years.

Nightspore at Tormance landed on an editor’s desk in 1920. After 15,000 words were cut and the title was changed, A Voyage to Arcturus appeared in 1,500 copies. Reviews were cold. Only 600 sold. The publisher declared Lindsay’s debut a failure. The magnificent dream of David Lindsay collapsed on the very first step, bursting like a soap bubble. But he refused to fall back asleep.

A Voyage to Arcturus

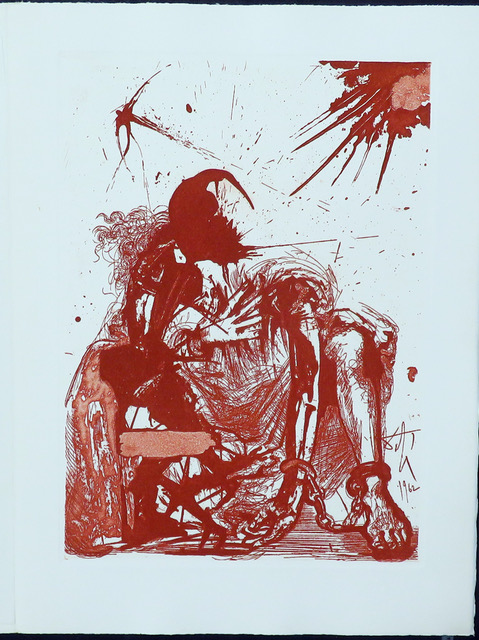

A Voyage to Arcturus is Lindsay’s first, best-known, and likely his greatest book. It tells of a journey to the planet Tormance, orbiting the star Arcturus. The hero, Maskull, wanders through its bizarre landscapes.

Following the trope of medieval mysteries, Maskull travels from place to place across a world lit by two suns, meeting colorful natives. Each encounter presents him with a dilemma, or an idea, that he must uncover, overcome, or surrender to. Like in a hagiography, he endures trials, tortures, and impossible choices in search of truth.

The inhabitants of Tormance worship Surtur, a distant, nearly forgotten god, and Crystalman, the deity of pleasure and beauty. Maskull’s Golgotha exposes Crystalman as a false, evil god who ensnares the people in illusions of beauty, preventing them from reaching enlightenment. Surtur reveals himself as Krag — the essence of Pain, the only true existence in matter, the one truth that shatters illusion.

Lindsay’s novel is an allegory, a gnostic manifesto. The Gnostics saw the world in reverse: the Demiurge, the biblical God, was evil for creating the material world; matter was evil, suffering, pain. Lucifer was the good god of the metaphysical realm. Lindsay was obsessed with the Gnostics and despised the materialism of the twentieth century.

A Voyage to Arcturus is an amalgam of genres: morality play, philosophical novel, science fiction — but above all, it is an explosion of imagination, a volcanic eruption of literary vision. Lindsay’s strange world (new organs sprouting, unknown colors, magnificent landscapes) bears witness to his imaginative genius.

During his lifetime Arcturus was forgotten, buried in a publisher’s warehouse. Only after his death did it rise again. C. S. Lewis, Tolkien, Philip K. Dick, and many others paid homage to the world Lindsay’s imagination had built. Harold Bloom, the most powerful critic of his age, could not resist: he wrote his own version of Arcturus, his only attempt at prose — and it ended ignominiously, even more ingloriously than the original.

Lindsay’s book is more an intriguing footnote than a central monument of literary history. Yet without it, perhaps neither Lewis nor Tolkien’s worlds would exist.

A Genius of Imagination, Without Literary Talent

Lindsay died in 1945, at the age of seventy, poor and bitter (although rare friends later spoke about cetain serenity in his old age). Thirty years of work yielded four books that failed both critically and financially, and three more that publishers stubbornly rejected.

There was a reason for this failure. His style was amateurish, dry, verbose; his sentences clumsy and unshaped. He wrote like someone imagining how “real” writers wrote. All his imagination remained trapped in dilettantish, immature prose. A sworn enemy of modernism, he scorned the stylistic innovations of Joyce, Woolf, and Lowry, attempting to drag literature back onto a Victorian track.

As his frustration grew, so did his books: thicker, heavier, less like literature. In his unfinished novel The Witch, striving to articulate his worldview in full, his prose ceased to be literature at all and became only kaleidoscopic philosophy.

Like Calderón’s Sigismundo, Lindsay awoke from his bourgeois slumber with a burning drive to create — and like Sigismundo, he created havoc in his own soul, trying to impose his absolute gnosticism on the world. When the world spurned his novels, his toil, his sleepless nights, he raged. Silently, inwardly, like a well-mannered, tight-lipped Scot.

Moloch of Art

David Lindsay is a tragic figure, a martyr, a victim of the dark side of art — that merciless Moloch. He knew literature was fickle, that literary success was fragile, that hope was a siren singing sweet and fatal songs. And yet he endured thirty years of renunciation, poverty, the contempt of all but a few colleagues, even the contempt of his own wife.

He was not Chekhov or Kafka, writers with another profession to fall back on. His tragedy was that he was not Chekhov or Kafka, yet he longed to be.

Years after his death came the book The Strange Genius of David Lindsay, a title Lindsay would surely have taken as an insult, almost a mockery. He was a writer of all or nothing. His biography, like his novels, provokes both admiration and pity. A Voyage to Arcturus is a book of extraordinary imagination; there his strange, bizarre genius is undeniable. And yet the characters are mere personifications of ideas, the style is dilettantish, and the reader is left saddened by the injustice of fate that befell this unfortunate writer — a genius of imagination without literary talent.

Lindsay, alas, is more a character from a novel than a novelist. He, who never knew how to depict writers, deserves to have a novel written about him.

All writers should read Lindsay and about Lindsay, about his sacrifice on the altar of literature. Like the prophets of old, he left worldly life and entered the desert, where he spent thirty years and brought nothing back from it — learned nothing from suffering — carrying only the ceaseless, maddening, instinctive need to write. Like Simon in Kiš’s story, he rose into the air to prove he was a god, and fell ingloriously back into the desert sand.

“And Dreams Themselves Are but a Dream”

Calderón’s Sigismund ends happily: he awakens from illusion and leads a victorious war for his throne. Lindsay had no such third act. In his gnosticism he insisted that life itself was an illusion, that the true world, the real and eternal, lay beyond matter and beyond those who worship it. He died in that conviction.

Sigismund, upon awakening, says:

What is life? A frenzy.

What is life? An illusion,

A shadow, a mere deception.

The greatest good is but small,

For all of life is a dream,

And dreams themselves are but a dream.

For Lindsay, Calderón’s Life Is a Dream ends already at the close of the second act — without catharsis, without triumph.

For more Apocrypha, read further: Bruno Schulz and the Republic of Dreams: Myth, Matter, and the Angel of History