If anything will bear witness to the complexity of our existence (when one day we are gone), it will be buildings and books.

Buildings testify to the monumental ambition of the human Body — the insatiable urge to conquer the material, to bring it under control, to touch the sky in the biblical sense. Everything constructed carries within it one brick of the Tower of Babel.

Books, on the other hand, will bear witness to an ambition of the human spirit no less monumental. From proto-books — rough papyri covered in pictograms and hieroglyphs, sacrosanct parchments bound in leather — through Gutenberg and the incunabula, to the digitized volumes of the 21st century, the entire spiritual, intellectual, and artistic journey of humanity is contained in paper and ink.

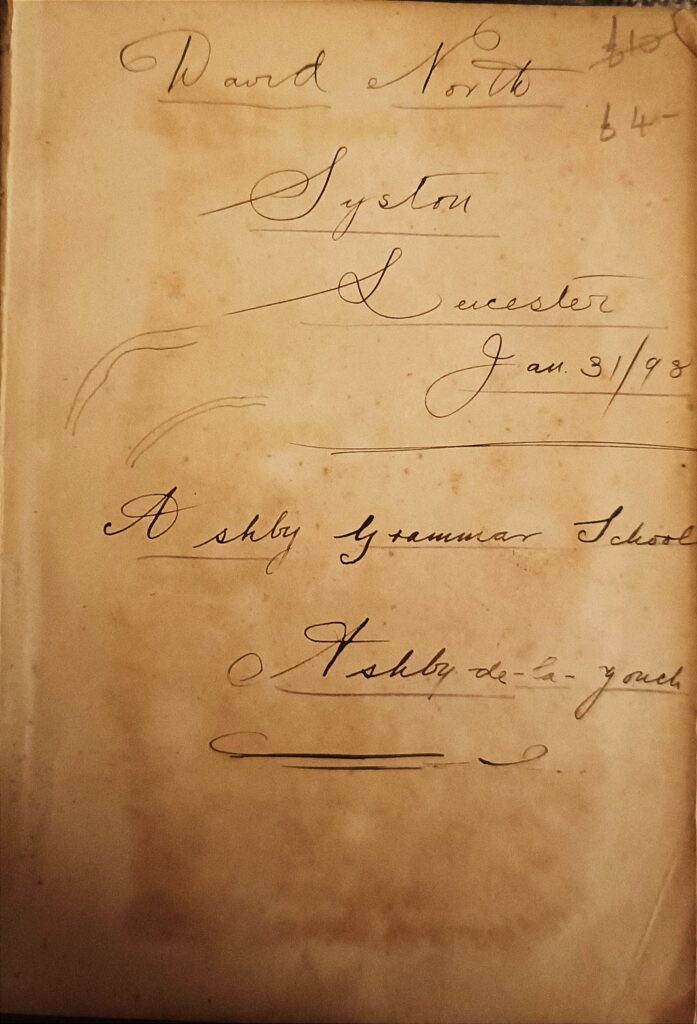

A book is, of course, neutral, amoral; it has no relation even to the idea inscribed within it. Closed, it sleeps on a shelf, in a chest, in a cellar, quietly and patiently waiting, drawing no attention to itself (perhaps it would even prefer we leave it alone). When some careless hand opens its covers, the book reveals its entrails without resistance, coldly and sleepily. The world inscribed in it is a potential, latent world. It is up to us to embody it with the force of our consciousness (and we do so, passionately). We attach our emotions, impulses, and unconscious yearnings to books like bells, which they ring into the deaf night. We love books, we hate them, we quarrel with them, and most terribly, we fear them. Then we burn them, stamping around the pyre with malice, thinking they suffer, that we are hurting them, that we are inflicting harm. But books do not care. They are present, they multiply at an unstoppable pace, and they have a single function which they fulfill with delicate precision: to guard against forgetting. Whom or what — that does not concern them. Books outlast people. Death awaits us without question, and most certainly the abyss of forgetting. That is why we dream of immortality, inscribing in books our own visions of the search for eternal life, knowing (even as we write) that the very book will most likely outlive us. They are more resilient than we are. All the gods of human history have revealed themselves through books, approaching human frailty with deep mistrust. Pantheons shift and shrink, but the gods persist — if only as information, as distant memories (like when, at the family table, we try to recall some long-dead relative).

Books preserve us; they are the urns of our souls, the magic lamps from which our ideas leap out, fragments of our personal histories, the remnants of our dreams. In their stubbornness, books endure through centuries; most escape the hammer of time, silently guarding the abstract treasure, the thoughts and language of people long since covered in dust.