Printed and written Traces

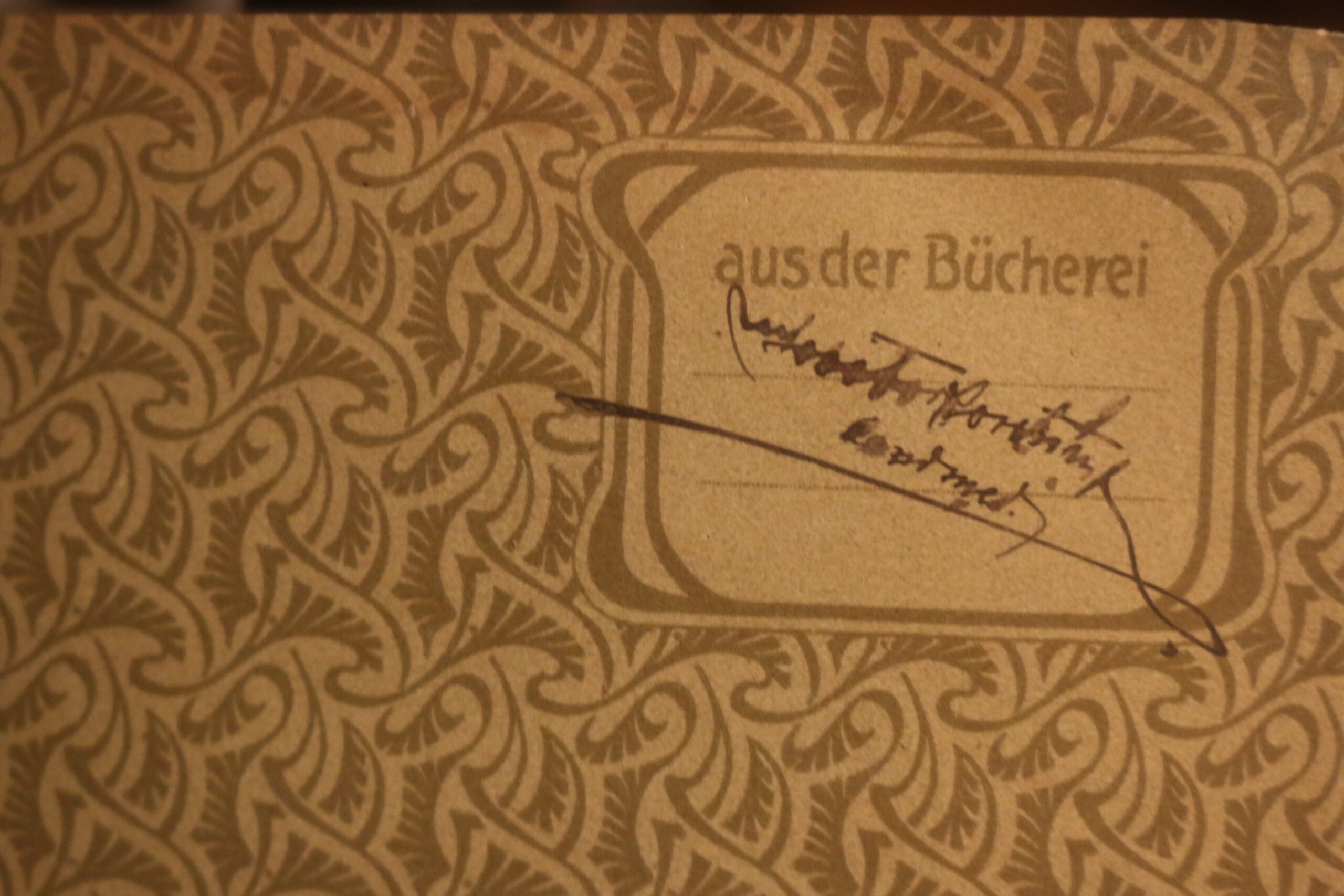

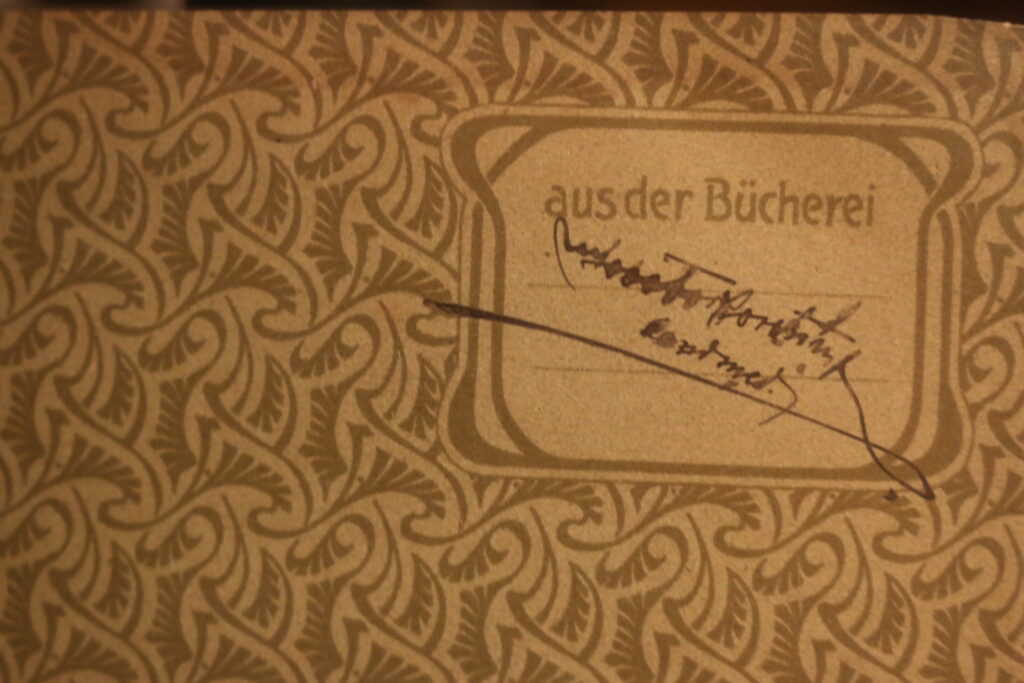

The invention of the printing press completely altered the character of the book. Separated it from the human being — its creator. The printing machine put an end to handwriting, which for centuries revealed the author or the scribe on the pages of a book. Handwriting, in turn, is an essential part of human individuality. Unique and unrepeatable, like a fingerprint or the configuration of an iris.

On a more abstract level, handwriting carries inherent sentimental value because, generally speaking, it outlives the person to whom it belongs. If someone has, during a lifetime, signed even a single receipt or a bank order, they have left a trace of their individuality that may outlive them. Individuality that, in the context of handwriting, reveals itself in details. In the slant of letters. The rhythm of the hand. Thin and thick lines, the pressure of the pen on the paper. Handwriting is, also, a short summary of our personality. A potential immortality.

Traces severed from us

By taking away handwriting as the book’s fundamental premise, printing freed it of its burden. Like a literary Tree of Knowledge, launched it into an independent, unknown world. On a metaphysical level, print emancipated the book from the human hand. That spiritual connection disappeared. The printed book is its own entity; reading it, one has the impression of conversing with a person, or at least with an entity that possesses its own consciousness.

And yet, the book — however much it might wish it — will never be free from the reader. The moment he or she overcomes the barrier of the covers ( because it is a bridge which is sometimes difficult to cross), the book yields to their eyes and fingers, unquestioningly and shamelessly, like a languid lover. Books accept their fate as given; they silently submit to the whims of readers, knowing that after one will come another, and another, and that across the centuries their pages will remember thousands of fingertips.

And readers are of many kinds. Devoted, careless, jealous, and democratic. Some guard a book possessively, others lend it to anyone. Returning to the question of immortality, I maintain that there is nothing sweeter than leaving handwritten traces in a printed book. In other words: to scribble in it.

This is the second essay in my Reading Chain series — meditations on handwriting, memory, and the traces left in books.

Start reading with Reading Chain (I)

Continue with Reading Chain (III)