The Marginalia in Books

Handwritten traces on the pages of books are as varied and colorful as readers themselves . Small doodles scribbled out of sheer boredom. Love notes, dedications, offensive or lascivious remarks. Abstract and accidental lines. Some handwritten notes even become amateur footnotes or comparative analyses, which is particularly amusing to read. Serious reading “with a pencil” (as Kiš called it), underlining in graphite or ink, completely changes the relief of sentences and the reader’s view of the page — which, of course, also alters the rhythm for the next reader. I have even come across handwritten debates in “manuscript footnotes,” a dialogue between two readers who never met and are separated by decades.

Marginalia as DNA

I do not tie these “reading chains” only to marginalia that contribute to the interpretation or understanding of a book’s content, but to every possible handwritten trace. Is there anything more striking than the accidental mark of a pencil? A faint involuntary line which the present reader knows was left by some fellow reader who is probably no longer alive? These traces, these “reading chains” embedded in a few meaningful or meaningless strokes of a pencil on a printed page, become the DNA of the book. Its biography. Sediment of experience. Also, our path to immortality.

Such traces, by their anonymity, resist oblivion. It is enough for a reader to think of the hand that once scribbled in the book they now hold, to wonder who that person was. For the proof of their existence, their individuality, is right there before their eyes. And as if by magic, that person is brought back into being. From just a few strokes of the hand, a few remnants of ink on paper, the reader will reconstruct in their mind an entire new person. Reading chains are seasoning for the printed text. An additional riddle. A playground for imagination. Also, foundation for one’s own imaginary world — of the person and the context in which the handwritten trace was made.

Marginalia of real people

Let me give one example.

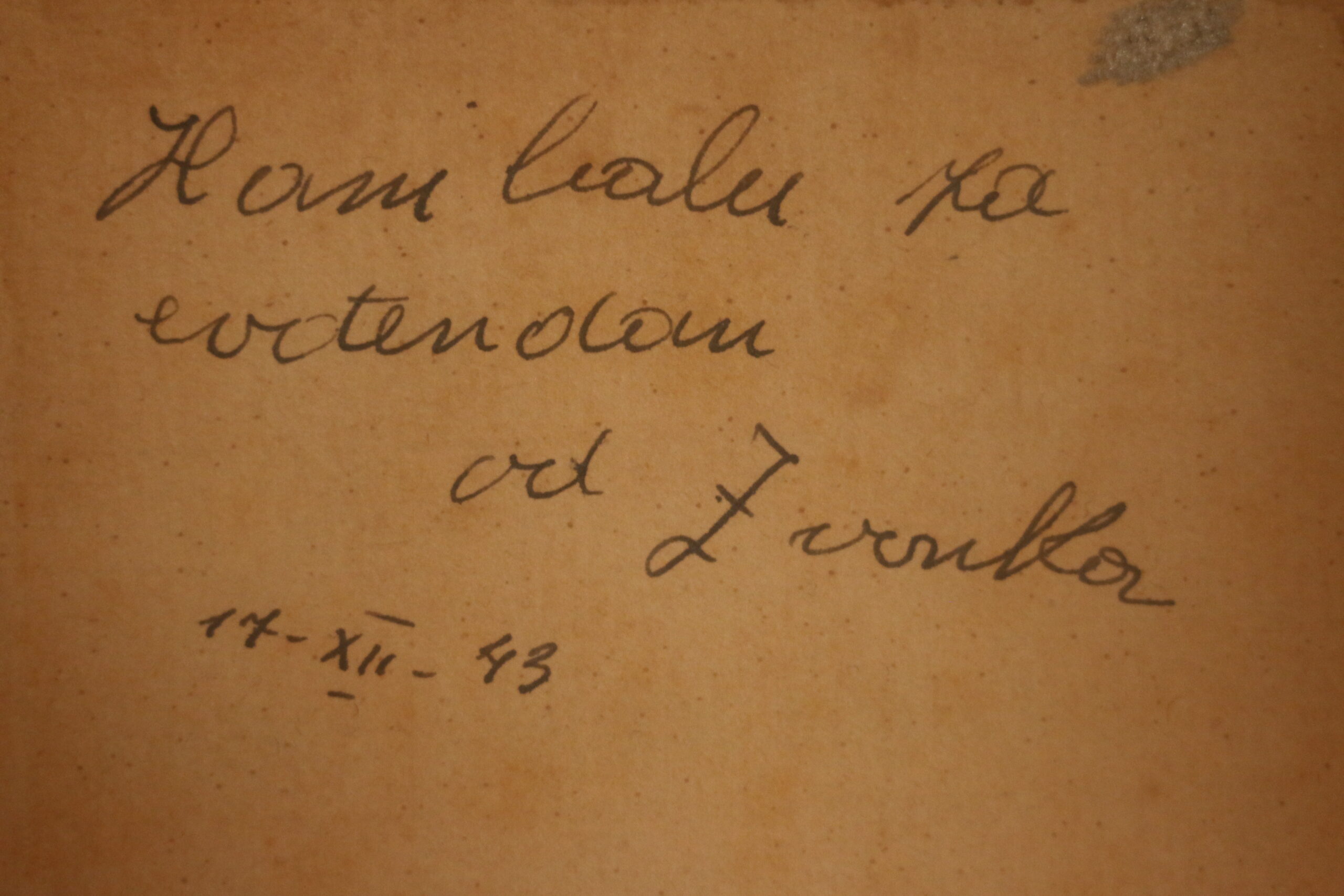

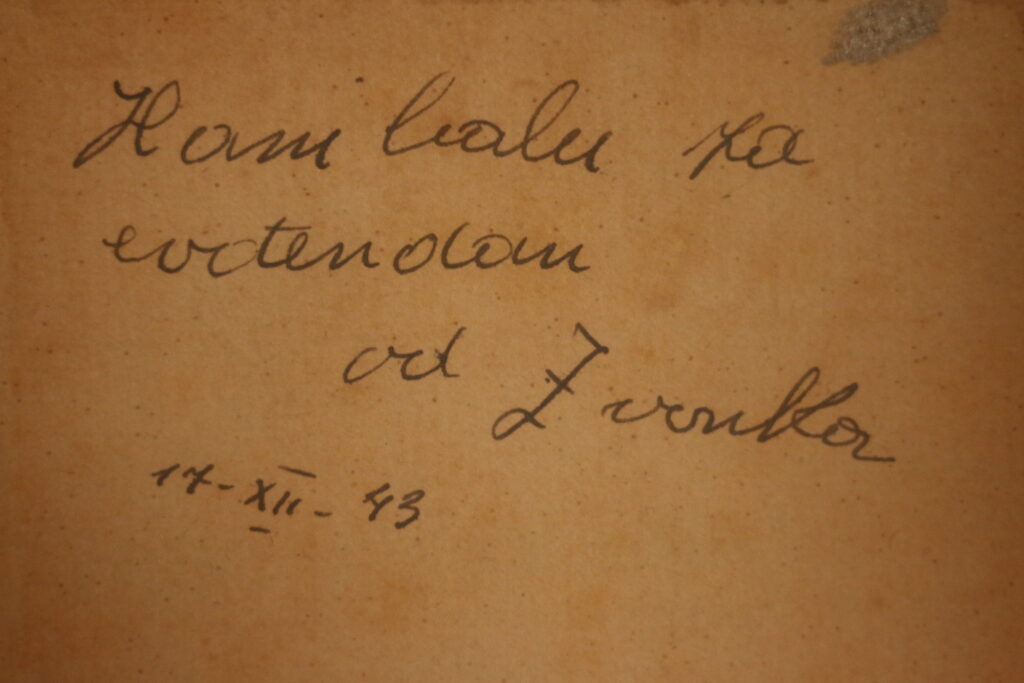

In a copy of The Kreutzer Sonata published in the 1940s (which I found at a flea market in Zagreb for a few kunas), on the first page it says: “For Hanibal, on his birthday, from Zvonko, 17 XII 43.” Hanibal and Zvonko. Were they close friends? Brothers? Relatives? Business colleagues? Did the gift of this particular book carry a hidden message for Hanibal, given that the book itself is not free of symbolism? A birthday gift in the context of the Second World War. The NDH. On which side were Hanibal and Zvonko? What did a birthday celebration look like in a time of war? A flood of questions begging for answers — enough to make one linger for hours on that first page, until Hanibal’s and Zvonko’s world slowly opens up like a lazy flower.

Marginalia as common fate

That is, of course, only one example. Countless times I have come across personal names written in elegant script on the flyleaves of books published in the late 19th or early 20th century.

For instance: on the flyleaf of a copy of The Merchant of Venice, published in 1898 and purchased in a Nottingham bookshop in 2014, it reads: David North, Syston, Leicester, Jan 31/98, Ashby Grammar School, Ashby de la Zouch. Written in fine calligraphy, this note conjures up the image of young David North from the town of Syston, a schoolboy in Ashby de la Zouch, and his unknown fate. When he wrote his details on the first page of what is now a yellowed book, to mark his ownership, he was only a boy, perhaps a teenager.

Did he suspect what awaited him? Two devastating world wars and a radical transformation of the world’s premise. Did he live through both? Was he a participant? A victim? Did he survive? We do not know. His schoolboy handwriting summons only the image of a boy who had no idea of what was coming. The common fate of all people.

Messages in bottles

There are many directions in which the interpretation of handwritten traces and “reading chains” can go. It is even a very seductive thing: there is something mysterious, detective-like about it. On a metaphysical level, it secures immortality for people as long as there are readers and books. But what I, as a reader, feel when I come across these messages from the past (like messages in a bottle) is comfort. Because they shatter the myth of the reader’s solitude. Thus, not only do I sink into the book and draw out one potential world into the light. I also become a mediator, a medium, through whom another sunken world blooms once more. Even if only for a moment.

This is the third essay in my Reading Chain series — meditations on handwriting, traces, and marginalia in books.

Go back to Reading Chain (II)

Or start from Reading Chain (I)